When I first started ROSEN I was not expecting to work with silks. Five years later, it seems to be the fabric I enjoy designing with the most. Aside from its reputation as a luxury textile, it is also one of the most versatile fabrics that is widely available today. When spun with other fibers such as cottons, linens, wools and polyester, silk elevates the feel, appearance and tensility of the final fabric.

As China is the world’s largest producer of silk fabrics, I am continuously exposed to the developments of silks that are available in the market, many of which are not often broached in fabric guides because factories develop new fabrics faster than it takes to publish a video or a guidebook. Therefore I decided to write my own guide to silks to share my knowledge with anyone who is interested in learning. It will be updated periodically whenever necessary. I have included their typical use cases specifically in the world of luxury fashion design, complete with existing examples that have been produced within the last decade, as well as my personal experiences working with them. In some instances, I have also listed the unusual ways in which they could be used to improve garment construction.

Silk – A Primer

Silk is a natural protein that is produced by silkworms. Commonly known as the king of fabrics, silk fabrics obtain its lustre because the yarns are spun from long continuous fibres. In the world of textile manufacturing, the longer the fibre, the more smoother the yarn will be, which is correlated to the sheen of the fabric.

Before going into the different types of silk fabrics, I would like to introduce the standard unit of silk weight: Momme, often written as MM or M/M. 1 MM weighs 4.34 g/m². In the world of silks, we do not use gsm because most fabrics are extremely light and it makes little sense to compare 20 gsm versus 24gsm. It is much easier to compare 5MM versus 10MM mentally. Light silks typically range from 5MM to 20MM. Anything over 30MM is considered a heavyweight silk. With that said, the average heavyweight silk weighs as light as the thinnest wool. The higher the MM, the higher the thread count and the denser the weave, so you can expect to pay a higher price for it.

Many of the fabric terminology that is often used on silks refer to the types of weaves, ie. satin, leno (or gauze), taffeta etc, hence why you will find that there are other materials that use the same terminology, such as nylon taffeta or polyester satin.

Table of Content

Silk Chiffon

Chiffon is perhaps one of the most ubiquitous silk fabric in the market. It is ultra light, soft and has a matte lustre. Its average weight typically ranges from 5-12MM, and as such it is one of the cheapest silks in the market. However, most designers who like chiffon often use it for ruching, pleating and shirring to create an ethereal layered garment while keeping it airy and light. They often use up a large amount of fabric, so it can incur as much cost as using a heavyweight charmeuse which is typically used in lower quantities than chiffon. Chiffon is perhaps the thinnest and most fragile out of all translucent silk because of the low thread count. It requires an adept pair of hands and patience to craft a multi-layered gown with this fabric.

Designers use chiffon for its transparency and creating feminine fluidity in motion. Think Grecian goddesses. One designer who favoured this fabric is Ann Demeulemeester. Maria Grazia Chiuri also used it heavily during her tenure in Valentino, then transferred it to Dior with her move.

Crinkle Chiffon

Crinkle chiffon is a close cousin of the chiffon that has a micro-pleated texture. It wears and behaves like chiffon does, and comes in ultra-light weight. Crinkle chiffon is used in designs that call for a more casual take on luxury. Due to its crinkled texture, this version of chiffon has a marginally higher opacity. Modern remakes of the Chinese Hanfu often uses crepe chiffon for a multi-layered design.

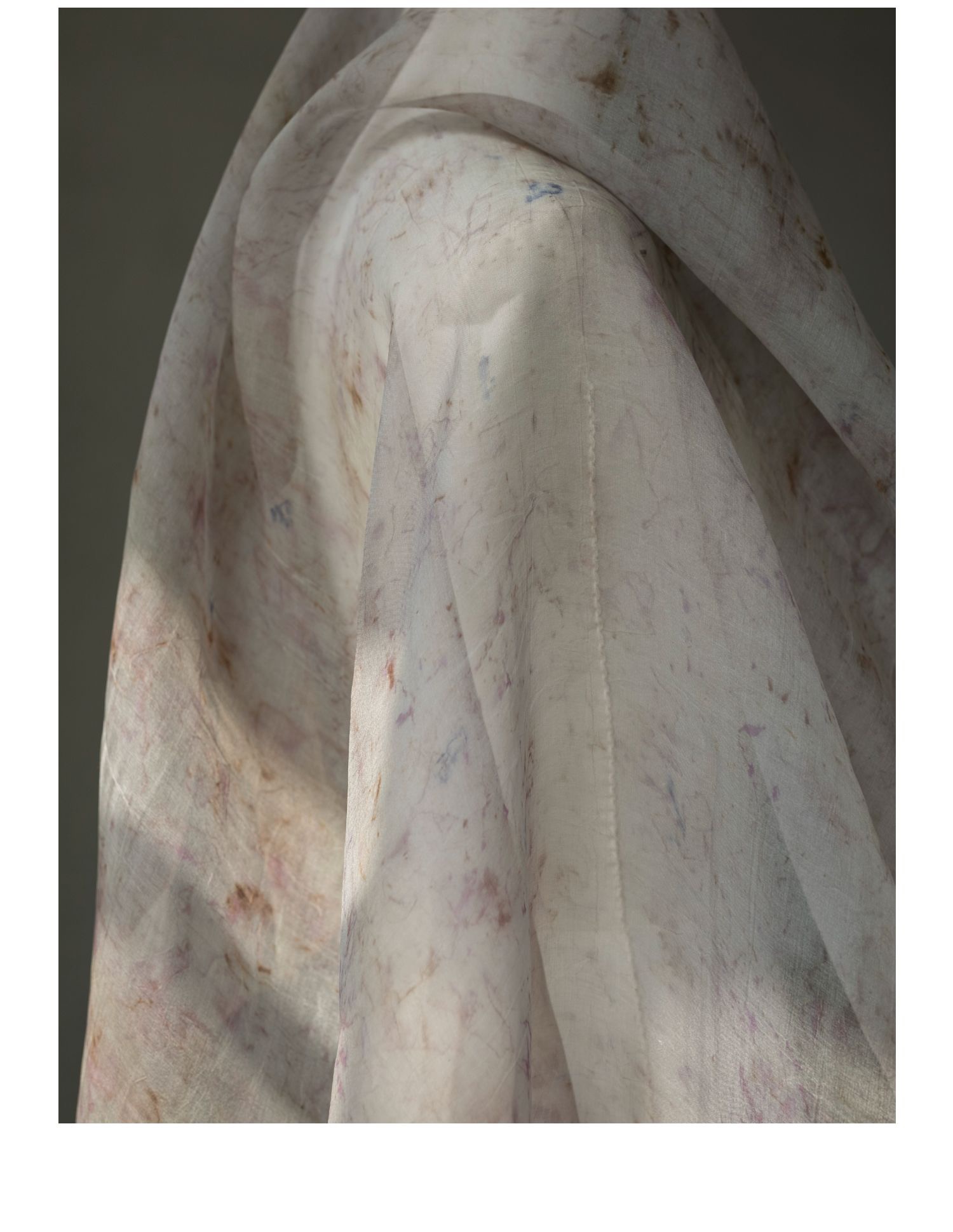

Silk Organza

For those who prefer a structured option when it comes to transparent silks, there is no better option than organza.

Organza is an easily recognisable fabric due to its crisp feel and transparency. Like gauze, mesh and tulle, it obtains its appearance from the leno weave. Considered an ultra light fabric, organza weighs about 5-12MM which is also correlated to the stiffness of the fabric. The lightest organza is a great in-between option for those who find chiffon to be too soft and standard organza to be too stiff. Heavy organza is excellent for garment sculpting and creating volumes.

Organza can also come in a satin form. In the world of textile, satin refers to a type of weave that produces high gloss, regardless of the material. As the name implies, satin organza has a higher shine than ordinary organza.

There is a rare type of organza called the gazar, which was Cristobal Balenciaga’s favourite fabric. This crisp fabric is twice as dense as an ordinary organza, which allows the garment to be made with huge volumes that defies gravity, blossoming outwards like the petals of a flower.

Top tip: When working with a soft outer fabric, organza is a great choice as interlining (the fabric between the outer shell and lining) that adds structure to the overall garment without adding much weight. Bridal designers often add organza underneath soft georgette or crepe fabrics when they want to create volume. By combining with the right shade of white, organza also enhances the colour of the top layer. I have used this technique myself to add rigidity and volume underneath a softer face fabric.

Silk Georgette

Georgette – though similar to chiffon from afar – is made of twisted yarns that give it a pebbly look and higher opacity than chiffon. Usually weighing about 8MM-12MM, it is commonly used as the middle ground option between chiffon and Crêpe de Chine, as it offers semi-transparency but also the appearance of a micro crinkles. A heavier version is called double georgette, which is denser and less translucent than its singular counterpart and sometimes comes with a more noticeable sheen. Double georgette tends to weigh 30MM and above.

Georgette works very well as drapey blouses, bias cut trousers and dresses. It is less fragile than chiffon so it can be made as single-layer garments. This fabric also serves as a popular base for digital printing and dyeing as the higher opacity brings out the vividness of the printed colours.

Shirt Dress

Crêpe de Chine

Crêpe de Chine (or crêpe of China) is one of the most widely used silk fabrics in luxury fashion due to its tasteful shine and fluidity. It is marginally heavier than silk georgette, weighing around 12-16MM for the standard weight, and 30 or 40MM for the heavyweight version. Its weave almost resembles georgette due to its twisted yarn, but think of it as the denser and more opaque cousin. Its heftier weight makes it a little easier to handle than silk georgette and chiffon. Depending on the final treatment of the fabric, Crêpe de Chine straddles between a matte sheen or marginal shine, but never glossy.

Top tip: while silk habotai (see below) is often used as lining in luxury garments, using lightweight Crêpe de Chine or heavier silk georgette raises the quality of the garment even higher. The production cost will be more expensive, but the final garment feels much nicer when worn than habotai.

with Ostrich Trim

Suspender Dress

Silk Habotai

A thin and light fabric, habotai is an ultralight fabric that is mainly used as linings, although some brands use it to as face fabric to keep costs down. Its typical weight ranges from 8MM to 12MM. In terms of pricing, habotai is one of the cheapest silks as it does not have the understated lustre of Crêpe de Chine or silkiness of charmeuse. It also feels more papery or cottony than other silks, despite being made from pure silk yarns.

Charmeuse

In the world of glossy silks, silk charmeuse is perhaps the most popular choice amongst luxury designers. Its satin weave gives the fabric the liquid mirror surface that was once prized as nightwear for kings and queens. Despite its weight it flows over the body gracefully.

This luxurious fabric requires precision and patience to fully draw out its finest qualities. Although modern fashion now demands casualness in everyday wear, charmeuse remains a popular option for lingerie, formal and bridal wear to this day due to its lustrous appearance and extreme comfort on the skin.

Charmeuse fabrics tend to come in 12-28MM. Anything over that would be considered heavy charmeuse, which commands a steep price in the market due to the yarn density.

Heavy Charmeuse

Satin Crêpe (or Crêpe-back Satin)

Satin crêpe is often mistaken for charmeuse as they are both very similar in appearance. The difference is noticeable when seen up close. The former has a twisted yarn texture despite its glossy surface, while the later has a traditional glossy satin weave. Most importantly, satin crêpe has a dull underside, which should be taken into consideration when making a single-layered, unlined open garment.

Watch the video below to see the distinction between the glossy face and the dull underside of satin crêpe fabric.

Duchess Satin

As the name implies, this silk fabric has a pearly shine, but while charmeuse is a fluid fabric, duchess satin is full-bodied, structured and heavier due to its high thread count. The heavy weight of the fabric is able to hold voluminous shapes and create sharp crinkles and folds. Duchess satin is mainly used for large gowns or precise tailoring as it has structural stability.

While duchess satin is commonly used in the bridal and couture industry, few have harnessed the striking beauty of duchess satin as well as the late alexander Mcqueen had done.

Mikado Silk

If duchess satin is expensive, the price of pure Mikado silk is astronomical. A densely woven fabric, it commands an even higher pricing as more raw material is used per square inch. While duchess satin is made with a glossy satin weave, Mikado is characterised by its twill weave. The end result almost resembles duchess satin in its stiffness but with higher fluidity and less gloss. Mikado is most suitable for heavy gowns that focuses on exaggerated silhouettes without heavy creases and folds, excellent for garments that emphasises fluidity. Due to the high price tag, Mikado is mostly reserved for the bridal industry. Few brands – such as The Row – have attempted to use Mikado for off-the-rack production. Needless to say, the retail price is much higher than other silk garments.

Silk Faille

Silk faille is a fabric that has horizontally-raised micro lines. These lines provide structure to the fabric while remaining lightweight which makes it an excellent fabric for exaggerated garments.

Silk faille has a unique appearance that is different from the iridescence of taffeta, dupioni and shantung. Its sheen is subdued and suitable for casual wear without compromising on the excellent breathability and comfort that silk is known for. The faille weave also comes in a silk-cotton blend (see further down) that gives the humble but robust cotton an elevated form of luxury.

Silk Taffeta

Taffeta was once a popular silk fabric that has fallen out of favour in modern times – until very recently. It was widely worn in the 19th century by the noble classes in Europe, then had a short-lived resurgence in the mid-to-late 20th century. While there are other silks that look almost like taffeta, its set apart by the swishy noise that it makes in motion. You can hear it coming before you see it.

A fabric that usually comes in 19-28MM weight, silk taffeta is lightweight and quite slippery to handle but it retains its shape well. Classic taffeta fabric has a two-tone iridescent appearance that gives it a recognisable hue. During the height of its popularity, taffeta was mainly used to create dresses and gowns that had prominent pleats, folds and volume, much like Duchess Satin. Despite its drop in popularity, some designers are bringing taffeta back in a burst of fuschia, neon orange and vermillion. Scroll through the slideshow below to see how the use of taffeta has evolved over time to its current modern iteration.

Silk Dupioni

Silk dupioni – an Italian creation – has a resemblance to taffeta as they are both iridescent in appearance, but it has a signature slubby texture. When compared to taffeta from afar, dupioni looks more fluid than taffeta, giving it a more uniform appearance.

Like taffeta, dupioni is often sold as a mid-weight silk that ranges from 19MM to 28MM. Volume can be achieved without needing a large amount of fabric or underlayers such as tulle. Today’s designers are now opting for a single-coloured Dupioni fabric with a subtler shine, so it does not give the iridescent contrasting hue reminiscent of the 80s.

Silk Shantung

The third iridescent silk fabric is the shantung. Originating from the Shandong province of China, shantung serves as the middle ground between taffeta and dupioni. It is not as loud (literally and figuratively) as taffeta, and has a smoother appearance than dupioni. It is commonly woven with yarns of different colours which gives the fabric an iridescent sheen. However, many textile manufacturers have been producing shantung with single colour yarns which gives it a similar appearance to charmeuse from afar, but still retaining its paper-like structure.

Shantung is a suitable fabric for garments that has a semi-voluminous silhouette or sharp structure. With that said, there are so many variations of silk shantung and dupioni in the market today that these two fabrics have become close substitutes of each other.

Tussah Silk

Tussah silk is vastly different from the lustrous and fluid appearance that silks are commonly associated with. The finest silks obtain its lustrous appearance because the mulberry silk cocoons are kept intact when boiled, from which long continuous yarns can be extracted. Tussah silk on the other hand, are made from silk cocoons grown in the wild that are harvested after the silkworms have chewed its way out, leaving behind fibres that are of different lengths. Spinning yarns from shorter fibres give rise to uneven and slubby texture on the final fabric while also reducing its gloss.

Tussah silk is perhaps one of the most diverse form of silks available in the market, though perhaps less so in the fashion industry as it is hard to standardise its appearance in massive quantities. They can feel as fine as a lightweight crepe, or as heavy as a rough cotton canvas. Artisanal designers often use tussah silks for its imperfect, rugged appearance that has its own charm to appeal to fans of quiet luxury.

Raw Silk

At first glance, raw silk has a similar appearance to tussah silk because they have uneven nubbly texture. However, raw silk has not gone through the degumming process that gives silk yarns its lustre, hence it looks like the matte version of a tussah silk.

Silk Noil

Another raw silk lookalike is silk noil, which is made from leftover silk fibres that have been through the degumming process. Like raw silk, it has a matte finish and nubby texture. Silk noil is not widely available in the market as most designers prefer to work with high lustre silk or tussah silk for those who want an artisanal look. Because they are made with leftover yarns, they are theoretically not as strong as other silk fabrics. The heavier versions of this fabric feels like coarse hopsack, which would make a durable, rugged-looking outerwear. Finer silk noil is most often spun into stretchy jersey fabric. When made into shirts and sweaters, they feel like a higher end cotton.

Silk Blends

Aside from fabrics made of pure silk, silks can be spun with yarns of other materials to create a rich array of textures and thickness by taking on the material properties of other yarns. Some commonly found silk blends include silk wool, silk cotton and silk linen.

Silk Wool

The marriage of silk and wool fibers have opened up a wealth of textile possibilities that have enriched fashion. There are so many ways in which silk wool blends can be crafted that it is impossible to show all available examples. Some silk wools are spun as worsted wool which makes an excellent summer-weight suit. Others can be as heavy as boucle and canvas. A common silk-wool fabric comes in the form of heavyweight georgette. It has the appearance of wool but the breathability and drape of silk.

In general, silk-wool blends of all weights tend to have excellent structure that maintains the shape and volume of a garment, making it a suitable fabric for voluminous dresses and outerwear, as well as structured suits.

Silk Cotton

This magical fabric blends the luxury of silk with the hardiness of cotton to create a versatile fabric that comes in many weights and textures. In its most common form, light silk cotton fabric is an excellent substitute for habotai when it comes to luxurious linings as it is also lightweight and feels comfortable on the skin. Heavier versions of this blend behaves in a similar way to cotton, with an added lustre that silk provides.

Silk-cotton comes in a wide range of weight, starting from 10MM which can be used as linings, 28MM for light outerwear and trousers, to as high as 40MM for a sturdy coat.

Silk Linen

Silk linen is perhaps a crowd favourite when it comes to showcasing what Mother Nature has to offer. The lustre of silk and the coarse texture of flax brings out a unique appearance that almost resembles tussah silk but has the hardiness of linen. Linen fibres also adds robustness to the fabric that lightweight silks often lack.

Silk-linen blends typically come in lighter weights from a soft 10MM, highly opaque fabric to 28MM sturdy blend that has a similar structure to organza.

Unique Silk Treatments

Silk is a natural protein fibre with unique characteristics that are suitable for unusual dyeing treatments. Since its invention four thousand years ago, ancient China – as well as its Italian and Japanese counterparts – had had plenty of time to tinker with various types of finishes to diversify and manipulate the appearance of silk fabrics in multiple forms. Here are a couple finishings that are noteworthy.

Sandwashing

Sandwashing is a treatment that can be done on some natural and cellulose fabrics, but it is commonly done on silks. By submerging it in alkaline mixture, the surface of the silk fibers are partially corroded, removing the sheen and leaving behind a suede-like texture. The uneven corrosion gives the fabric a vintage patina. For those who dislike the high gloss of silks, this sandwashed treatment is an excellent alternative as a fabric that feels extremely soft on the skin.

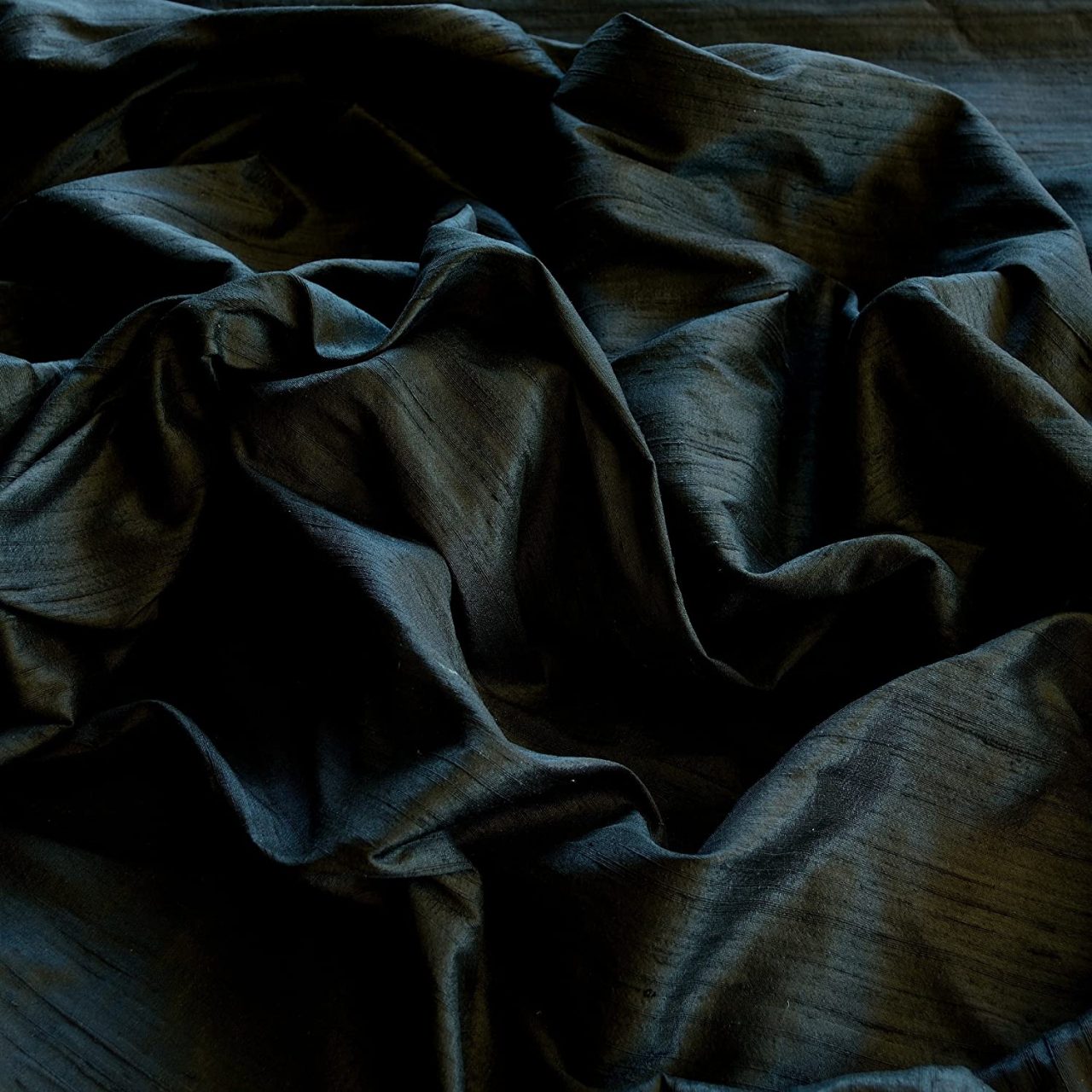

Xiangyun Sha Dyeing

Out of all the treatments available in the market today, none other comes close to the richness of the exquisite Xiangyun Sha. It is characterised by its dark – often pearly black – face side, and a brown rust colour on the underside. This dyeing technique combines all the elements that only Mother Nature can provide, from strong consistent sunlight to water to the nutrients from the ground and the river. Unlike modern chemical dyeing, there are no machines involved in any steps. The exposed brown edges of the fabric roll is a tell-tale sign of the manual labour involved that will inevitably leave imperfections in the final result.

Early records showed that Xiangyun Sha was mostly made of leno weaves (common leno woven fabrics are gauze, tulle and organza) which explains the name, as sha refers to gauze-like materials in Mandarin. Today however, this dyeing treatment has been tried on other silk weaves, which can range from raw silks to heavyweight charmeuse.

Xiangyun Sha originated in Southern China many centuries ago, specifically in the Guangdong region where the sun is strong and the Pearl River Delta is rich in iron, which contributes to the colouration of the silk. Silk rolls can be sent to these workshops either undyed or pre-printed or with jacquard weaves. This dyeing process is extremely labour-intensive – requiring teams of thirty to fifty people – and and can only be done within the short window of summer and autumn, hence why it is not easily obtained and also extremely expensive in the market.

This dyeing treatment produces results of unimaginable beauty that cannot be replicated from one batch to another. Only those who are willing to appreciate the imperfections are drawn to these silks.

An Ode to Silks

I designed this kimono robe as a canvas on which I can showcase the beautiful silk fabrics that I love. Its reversible construction is inspired by men’s Haori which is muted on the outside while hiding a beautiful hand-painted silk lining. With that idea in mind, I made the face side of the robe sombre and the underside vibrant.

The navy body is made of a slubby tussah silk with a subtle shimmer on the outside, in a colour that could be best described as midnight. Its volume is maintained with a hand-dyed silk organza on the front, and an ultra heavyweight 80MM charmeuse that has gone through a Xiangyun Sha dyeing treatment that gives it a signature washed brown colouration. The robe is accented with crinkled triacetate trims and jacquard collar and hem.

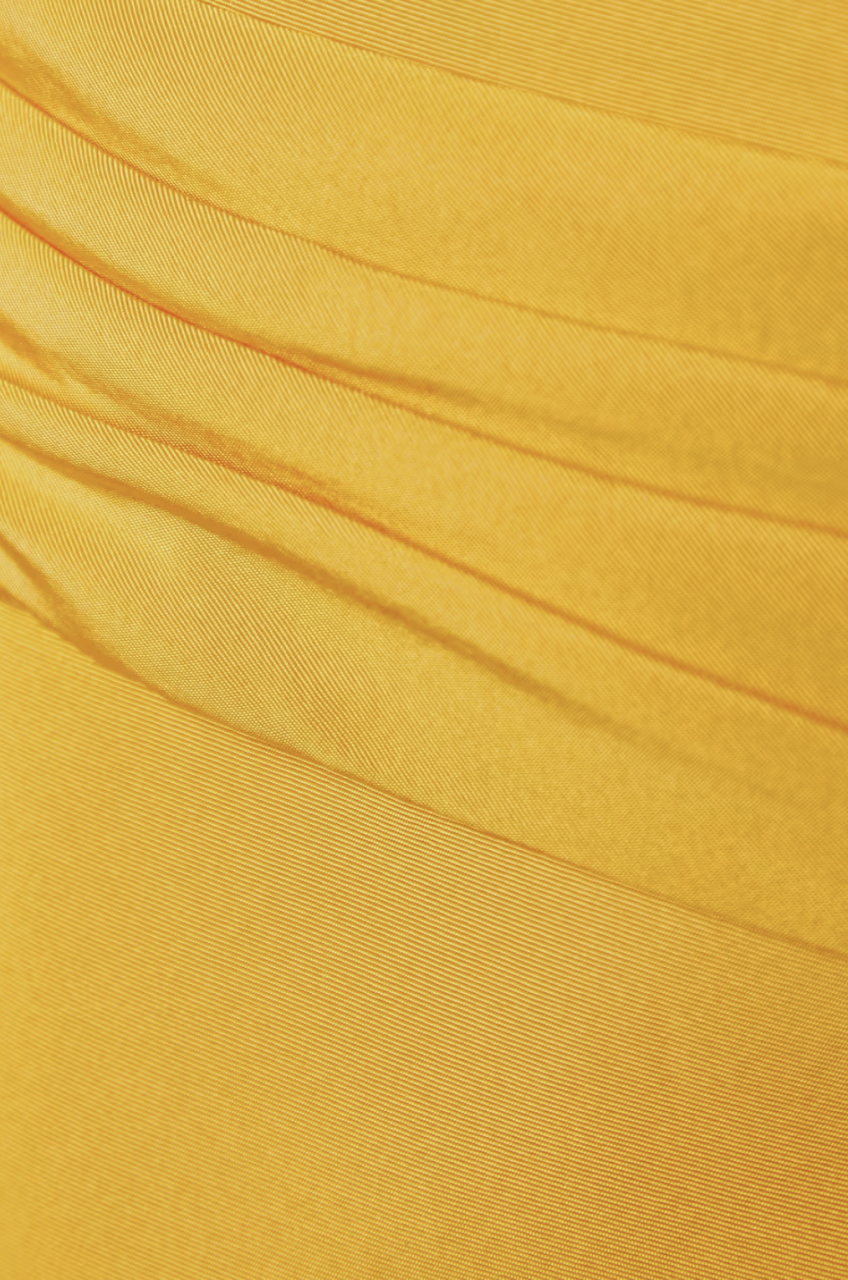

The maxi dress is made of medium weight silk-wool blend fabric (32-36M) which retains volume well without hampering motion.

A Few Last Words

Silk is undoubtedly one of the most versatile and luxurious fabrics Mother Nature has provided for us. However, it is not exactly the easiest fabric to work with. No matter the weight or weave, it requires experienced hands and instinctive minds that can only be shaped by years of experience working with this fabric. One has to be able to control the flow of fabric under the machines, handstitch in the right places or use couture finishings, pick the right threads, facings and interlinings to complement the wildly variable characteristics of silks.

I wrote this guide to share the knowledge I have gathered over the years working with silk garments. Whether you are a designer, sewing hobbyist or fashion enthusiast, understanding the properties of as many fabrics as possible opens up a world of design and styling possibilities. Unfortunately, outside the bridal and couture industry, silk is increasingly being replaced by its much cheaper lookalikes made of polyester and rayon so that luxury brands can carve out larger margins without changing their business model that relies on overproduction. That leaves new generations of fashion consumers, students and and designers with less reference for fashion that prizes craftsmanship and high quality materials. I hope that this guide can assist in lowering the barrier to entry that silk often poses to newcomers.

Although this guide has strived to be as comprehensive as possible, there are lesser-known types of silks that have not been covered such as Moiré and silk cady, or the self-explanatory silk jacquard, silk velvet and stretchy silks. I will keep updating this list if there are new popular silks that have arrived in the market, or if there are requests for specific ones. So if you like this guide that I have written, feel free to bookmark it and share it with those who might benefit from it.

Thank you for this guide. I think this is one of the best explanations of different silks and uses that I have come across.