For all its talks about diversity and inclusivity, fashion is losing sight of its primary imperative – a vehicle for independent creativity that the human minds can offer in materiality. As the world is increasingly becoming globalised, fashion is converging into a singular point of view dictated by those who has the financial power to influence the masses.

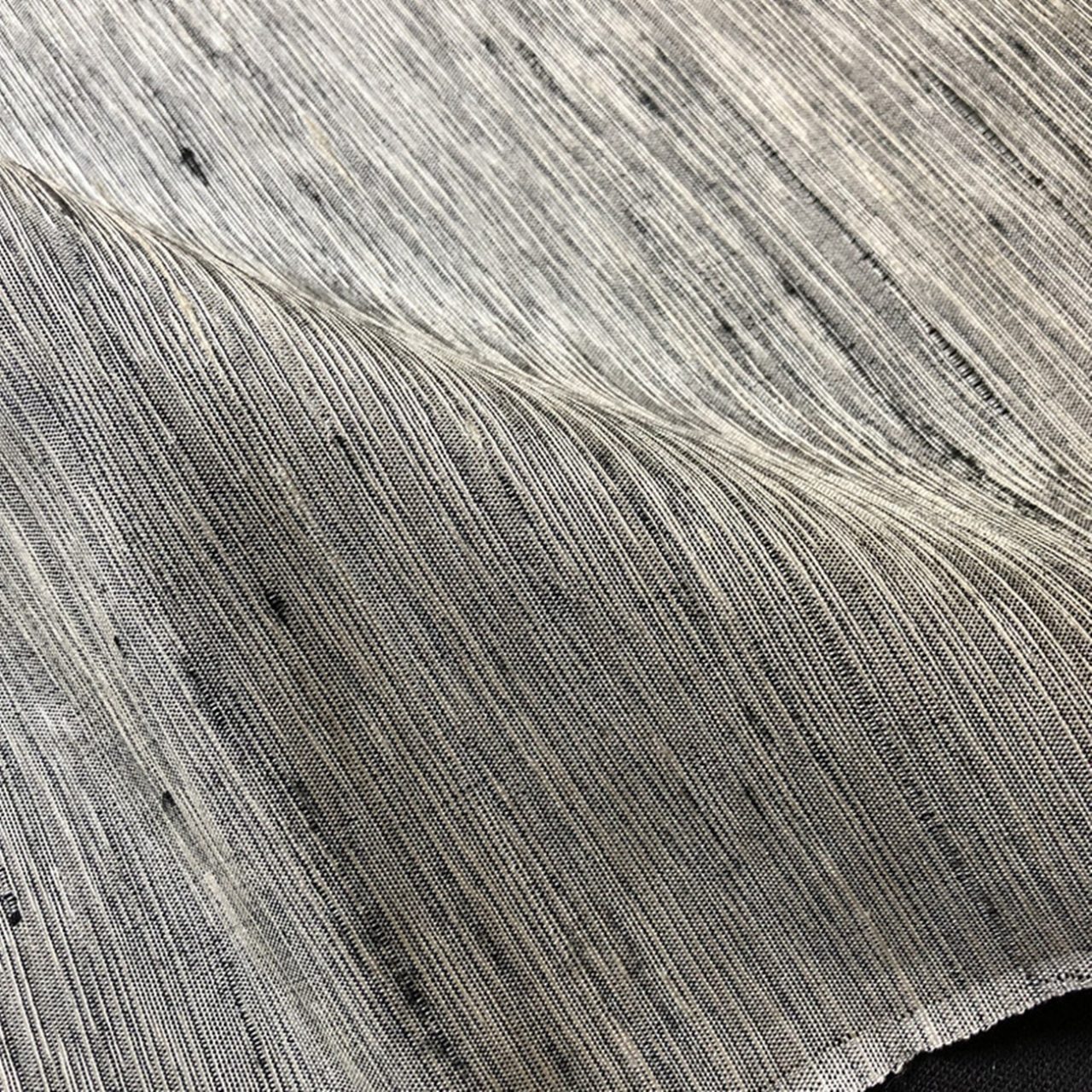

On the periphery of Shanghai’s central area lies a mall that houses small offices of fabric wholesalers. It is the sort of shopping I like to do – in which I consume inspirations in order to create. There are about two hundred or so companies in this mall, much smaller than its Guangzhou and Shaoxing counterparts that occupy several buildings, and a couple of post codes.

In order to compete with one another in this expensive city, these wholesalers have to pick the best of the best from what the entire country has to offer, which is not an easy task. The result is that, within this small space, I can be looking at the best silk blends being made right now, to experimental wool treatments, to modern blends of fabrics that combine the best of what each yarn has to offer.

Yet it pains me to say that very few of these fabrics will be seen by the typical consumers. On the rare occasions I pay a visit to physical stores – from fast fashion to sportswear to household luxury names – the range of textiles that I see are as diverse as a group of panda in captivity. The majority of customers are subjected to ten different shades of blue denim, sheer polyester chiffon dresses, lycra gym wear or ultra matte nylon rain shells. Though the colours and built quality may differ, without the aid of branding, these garments hardly possess any unique differentiation from each other. The more well-known a brand is, the less adventurous they become. As a result, most ordinary consumers are not aware of what they are missing.

When I was in university, one of the major questions of international economics was globalisation and its effects. At the time, debates on whether globalisation will bring about convergence or divergence remained inconclusive; will we be seeing cultures merging into homogeneity, or will we be celebrating plurality in aesthetics and philosophies. Ten years later, we finally have the answer.

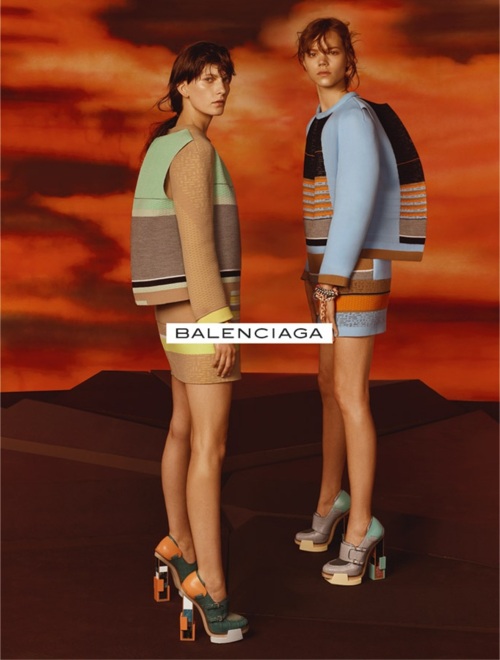

Balenciaga of fifteen years ago made garments in beautiful, sometimes weird materials that few could replicate. Historic names like Fendi and Dior promulgated French lace and Scottish wools; Valentino with Italian silks. The age of goth ninja – as ridiculous as the term might sound – brought forth washed wools, jerseys and linens. Ann Demeulemeester showcased the thinnest washed lambskins as soft as a baby’s touch. Issey Miyake pushed pleated polyester while Comme des Garçons did wonders with its boiled wools and shrunken synthetics. I loved the leathers that Rick Owens experimented with from one season to the next. Those were also the days when Jan Jan van Essche and Damir Doma – renowned for their textured fabrics – were names to watch for. The world of fashion was richly diverse in its physical properties. Today, they would be considered out of touch with the post-modern, globalised post-pandemic world we live in. Mainstream fashion industry is now run with transnational-style corporatism and aesthetics, ie. corporatism style that has put the marketing cart before the horse of creativity, and aesthetics that turned people into walking advertising boards. Everything has to be flat, untextured and sterile.

The Victory of Marketers

Fashion trends often start from the streets spearheaded by youth cultures. It so happens that those growing up post-2008 crash are now in a more precarious financial and mental space that is more readily exploited by advertising. Being young, they have lower spending power, and in the midst of their journey of self-discovery within disappearing communal and familial support, they have a strong desire to belong to the aspirational class in order to find love and respect. Much like a gang member who has been tattooed, branded merchandise is the cheapest method to signify one’s taste and want for membership into a tribe. And as we have observed since the youth revolution of the 60s, what teenagers wear will eventually trickle upwards to the mainstream. This trickle-up trend was momentarily curtailed in mid-2000s. In that Golden Decade between 2005 to 2015, designers across Europe all the way to Asia wielded power to bless fashion fans with the grace of their creativity and ingenuity. But the inevitable had to happen. The economic mishandling of post-2008 Great Recession bore its fruits a decade later, taking power away from small players and creatives into the hands of their marketing and management overlords.

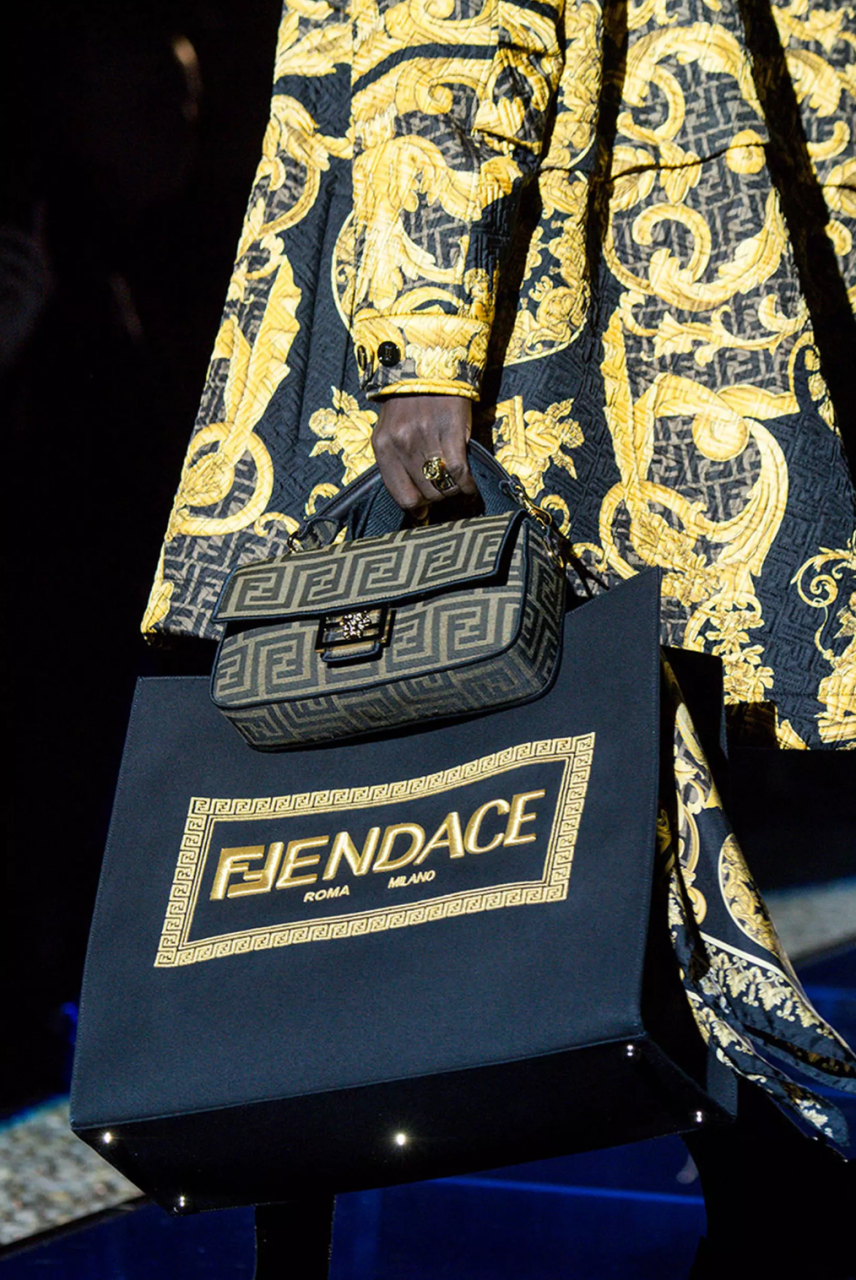

Today, what social media wants is what the consumers will get. As social media wields its heavy influence on buyer behaviour, the prominence of logos have remained unchallenged, especially amongst the younger market who are predominantly heavy users of social media. From the streets of Los Angeles to the malls of Singapore, consumers of all ages are decked in logo-ed t-shirts, puffers, sneakers and handbags. Notice that logos are usually printed on flat fabrics. Any unusual textures and warps in the fabrics will reduce their prominence. That is why cotton and plain-faced synthetics have become the go-to option for marketing-driven business strategy.

Branding also comes in the form of photogenic lifestyles. When the pandemic arrived, lockdowns, combined with expansionary monetary policies that gave tech companies advantageous financial positions, saw tech magnates growing their wealth exponentially. The leaders of these companies gained the spotlight – their lifestyle revered, their brands of choice examined. As the new elites of Silicon Valley wanted to differentiate themselves from their parents, it led them towards plain softshells that brandished a recognisable logo on the upper chest or arm as a callsign to other fellow execs.

From the switch to working from home to a growing preference for outdoor activities, the pandemic saw the meteoric rise of sweatpants fashion and esoteric hiking gears. These garments share a similar appearance because they are made of plastic polymers that have been spun, woven, dyed and coated in specific ways to deliver performance that center on stretch, water-resistance, and airflow. Another reason for the homogeneity is that Gore-Tex has market dominance over performance fabrics due to its first-mover advantage in the outdoor industry. It has now successfully infiltrated the youth market via aggressive collaborations with every other known streetwear brands, thanks to its PR exercise with BEINGHUNTED.

Fashion – an industry that was once led by risk-taking creatives – are now led by marketers and merchandisers, either under the diktat of two French industrialists who happen to have a hobby of collecting fashion brands, or American institutional investors. These number crunchers are the ones defining modern aesthetics for us. Risky ventures in individualism and experimentations are subtly discouraged to make room for conformity that generates fast returns, as a result of which luxury is barely discernible from mass-market fashion. Instead of leading their flocks to their respective fountains of creativity, they brought everyone to the same drinking trough.

Long-Term Ramifications

Wool does not behave like nylon in the same way that rayon is vastly different from silk. A pleated polyester drapes differently from its laminated counterpart. Each fabric and its respective treatments require hands-on working experience in order to gain familiarity. Learning takes time, time is money – money that corporate managers do not want to expend on their employees for fear of diminishing shareholder returns. When every successive generation of designers is being siloed into using only commercial textiles, the industry will be facing a dearth of knowledge in clothing manufacturing.

I foresee the same happening with the younger generations who are interested in fashion. There have been numerous occasions in the last few years in which I notice that those who are experimenting with making their own garments are taking inspirations from similar sources. It comes as no surprise that those who are not privy to the inner workings of the system, or are located close to fabric wholesalers, or have access to a diverse archive of fashion history will gravitate to what is easily found in public domain. The more homogeneous the public domain becomes, the less source material there will be for future generations to learn from.

Ultimately, the major loser in this ecosystem is the consumer. For the price consumers are paying, they should be given the chance to experience a wide array of what textile manufacturers have to offer. The market does not reflect that at all. Fast fashion relies solely on the lowest end of polyester while luxury brands are increasingly using flat synthetics, as can be seen by the offerings on Net-A-Porter.com. For anything remotely interesting, brands like Valentino and Alexander Mcqueen offer cotton dresses for $3000, while silk garments are now costing close to $5000, far above what the middle class can afford. While there are smaller brands offering adventurous fabrics within the sub-$1000 range, they do not have as large a reach as their more well-known competitors. At the rate we are going, only the time-rich and/or financially-secure upper echelons could brush against anything creative.

As consumers are being groomed to find value in branding as opposed to materials and craftsmanship, their knowledge in product quality and reference for materials will diminish over time; a trend I am now observing from my own pool of customers. Younger customers gravitate towards plain-faced synthetics that they are familiar with, while those who still sought unusual materials tend to be in their thirties or older.

At a time when large corporations dictate the bulk of fabric orders, textile manufacturers will focus on what their customers ask for in order to survive. Factories will switch to simply making cottons or synthetics to stay competitive. Over time, they will lose the technological know-how to produce fabrics that are no longer in demand. Just as lace-making is now on the verge of extinction, we might just see the same with other labour-intensive fabrics such as wool.

It is no secret that independent creatives and fashion brands are becoming endangered species, struggling to survive against conglomerates in the age of neoliberal plutocracy. This ‘blandification’ of textiles is but a symptom of the industry’s spiral towards homogeneous mediocrity which we are witnessing with every passing fashion cycle. As a contrarian designer, I am doing my utmost to balance the demands of current times while simultaneously introducing fabrics that differ from the norm. Even if individually it is impossible to reverse the machinations of trillion-dollar marketing, we should do what we can to keep true diversity and creativity alive in this industry, with the hope that fashion will rediscover its true purpose again one day.

superbly said. thank you

Wonderful post.

I’m someone who has recently taken up sewing and I’ve found that my biggest issue is finding the right fabric. I’m not particularly drawn to most of what I’ve seen in your traditional fabric store.

I would love to purchase fabric from manufacturers who are creating interesting textiles but I would imagine that they’re waiting for buyers who make large orders and pay for exclusivity rather than someone who would want a few yards of fabric (if I’m mistaken, please let me know). I just wish it was easier for us to purchase quality textiles in small quantities.

I also would hate for all of the knowledge gained over the past few decades to disappear and I hope there is a knowledge base somewhere.

Hi Ali,

Thank you for your kind message. As someone who used to live in cities without a garment manufacturing sector, I can empathise with your situation. There are however, places where you can get deadstock fabric. They are called jobbers and I can see that there’s a growing number of them online. There might also be one or two in your vicinity. Jobbers have more varied options than fabric retailers as they are selling excess fabrics from garment production. Most importantly, there is no minimum quantity.

Excellent write up as always. I always look forward to your posts.