Prologue

Four months ago, I embarked on an ambitious journey to design ROSEN-X garments I would never have dared to do just the year before, owing to the fact that my technical proficiency did not match the standard I wanted to achieve. But 2020 has been the year where major changes took place at ROSEN; expansion happened, so did progress in product development.

Before 2020, I had no hired assistance for production. For every idea that was released into the world, two or three had to be shelved. Many of those ideas did not pan out as I had hoped due to certain shortcomings on my part. I did not possess the technical language that I could communicate to the manufacturers in order to do my designs justice.

2017

2018

2019

2020

In early 2020, I hired a patternmaker who graduated just the year before. In fashion I have realised that duration of work experience does not necessarily correlate to quality of work. Despite his short work experience, I brought him on board due to his conscientious attitude, organisational skills and mathematically-proficient mind, with none of the naive ambition of grandeur harboured by many young fashion graduates (oh the stories!). His contribution has allowed me to explore ideas that were previously unreachable due to my limitations in technical proficiency.

Even with an additional mind and an extra pair of hands, the path towards the finish line is never straight and true.

Fashion and Its Enduring Myths

Fashion sells dreams to its consumers as well as its aspirants.

Whenever I watched fashion documentaries, every idea began with a flamboyant, colourful sketch – be it by Karl Lagerfeld or John Galliano; most of them with much flourish and very little tangible details – then whisked away by the première (head seamstress) of the atelier. The rest of the design team took care of fabric, trims, construction and production. Two weeks later, the outfit was ready.

Karl Lagerfeld Sketch

Completed Haute Couture Look

These documentaries only sought to heighten the role of creative directors, that they are the sole harbinger of beauty and splendour. In actual fact, their half-drawn visions would not come to life if it were not for the hard work of dozens of unnamed artisans and department heads doing their best to interpret what the creative directors were thinking.

Contrary to popular belief, it is actually uncommon for fashion designers to be proficient at sewing, let alone knowing how to construct a garment from start to finish. Modern fashion designers have limited range of hands-on skillset (unlike the luminaries of yesteryear such as Cristóbal Balenciaga and Azzedine Alaïa). It is an acceptable industry standard because the role of the designer has changed. They are valued for their vision and creativity, not for their ability to drape and sew, even if some do maintain that knowledge like Issey Miyake and Rick Owens. What they are not capable of doing, there is someone out there who can fill that gap. Conversely, someone who is more proficient at technical production but has a terrible taste would make more money as a technician or patternmaker. As a side note, skilled patternmakers tend to earn more than (non-celebrity) designers.

A fashion designer who works in a large production team do not have to overly concern themselves with the technical implications and production of their designs. Material procurement, budget constraints and technical difficulty – those are other people’s jobs. Their role is no more glamorous than their fellow colleagues who are patternmakers and garment technologists. It is only in fashion documentaries and instagram-fuelled influencer culture where we are taught otherwise.

I have spent a lot of time writing to dispel the myth of working in fashion industry. Behind the white curtains, there is little glamour to observe but plenty of hard work, sweat and tears. The typical fashion design entrepreneurs do not have that kind of resources that allow them to spend all day making pretty drawings and petting fabrics. They have to fill the roles of technician or business(wo)man if there is no budget for hiring. If you are interested in producing your own clothing line, this is the harsh reality that you have to face. While the typical route to fashion begins by going to fashion school, going into debt for a payoff that is uncertain may not be a financially prudent idea. And time and time again, we are reminded that some of the most successful designers did not go to fashion school.

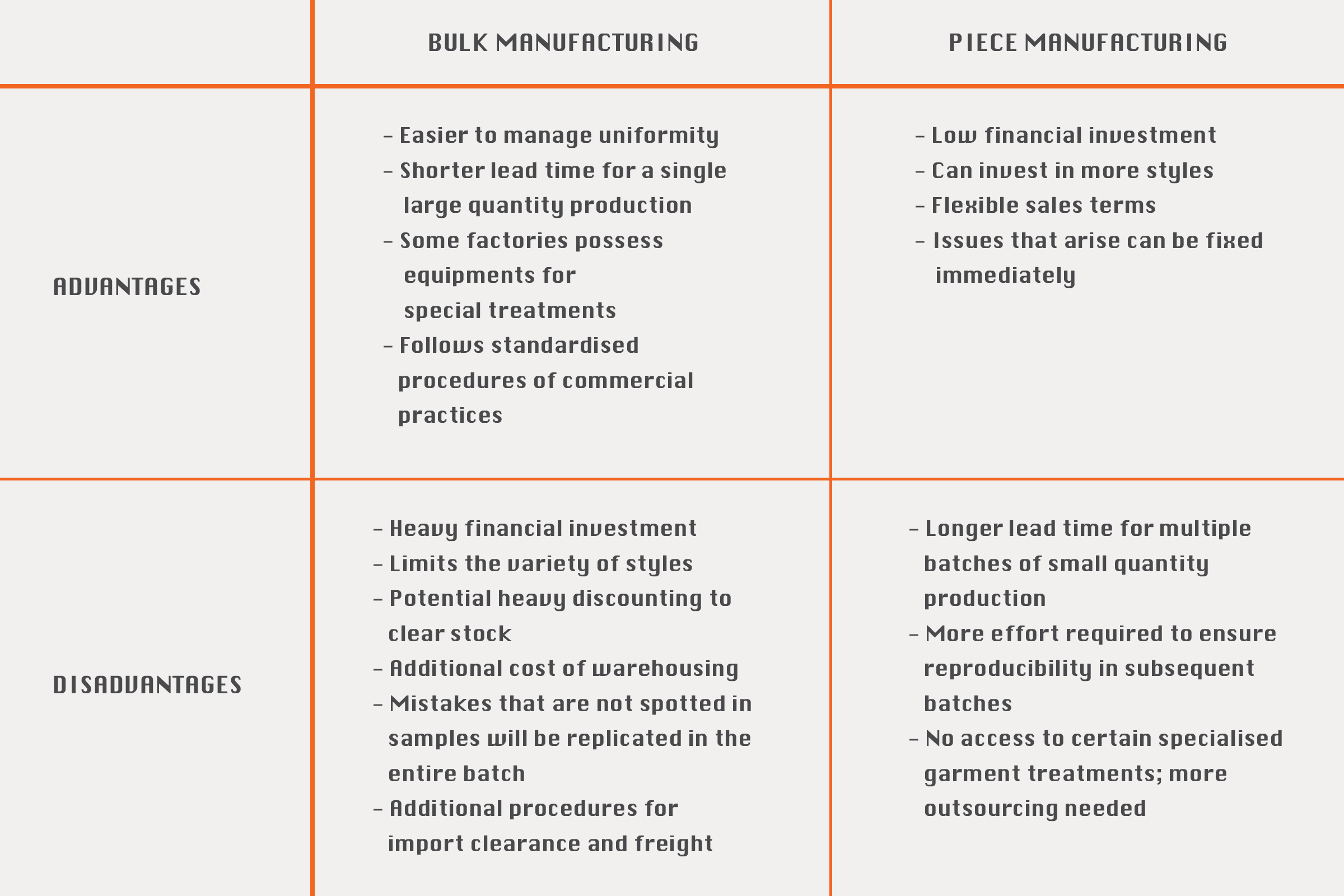

A Simple Guide To Manufacturing

This guide is thus written for those who have never been to fashion school, who do not have a production partner or team to work with, and are not awash in investors’ funding. I wrote this based on my personal working experience, coupled with lessons from the school of Lean Manufacturing (ie. prioritise efficiency, produce in small batches) and Just-in-Time Production.

A. Start with Existing Catalogue

Think bomber jackets, fishtail parkas, tunic shirts and tailored trousers.

I begin this guide by introducing a tried-and-tested method practised by brands who pursue speed and are not looking to make unconventional clothing. And as one who is simply starting out for the first time (or even the second or third), making overly complex clothing is not advisable until you have learnt the rules of construction, fit and silhouette before proceeding to break them. Let’s face it. You did not graduate with an MA in Fashion Design from Central Saint Martins. You have not sewn a straight line everyday for ten years. You don’t know which parts of the garment need to be fused with interfacing. You cannot deconstruct before knowing how to construct. Be practical and acknowledge your limitations.

This should be an exercise in honing your taste. Most sellable designs begin from conventional and ubiquitous garments. They are also associated with comfort, convenience and ease of care. What makes them different is the designer’s taste in fabrics, colours and trims, and a tweak or exaggeration of the silhouette. A person possessing a refined taste can make a ubiquitous garment look fresh with their own perspective.

Why A Factory?

Factories already have the expertise in making specific styles year in year out. They are best suited to advise on fabric, fit and production. Some of them have catalogues of existing designs that you can tap into and modify according to your taste.

Quite often, when we think of factories, we think of hundreds of workers toiling away on the sewing machines.

While large-scale garment factories still dominate, they are gradually being phased out to make way for smaller factories who are open to accepting low Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) of 100-500, and even smaller workshops who can produce 30-50 pieces at a time. While I am not too familiar with the current garment industry situation in the US, small to medium-sized factories can be found across Europe; India, Bangladesh and Indonesia factories tend to be on the larger side due to their low labour cost. China and Vietnam boast a mix of factories and workshops of all sizes. While China is phasing out heavily-polluting low-cost manufacturing as part of its initiative in going carbon neutral in 2060, there are now more small factories and workshops who are willing to make extremely low quantities, high-value products for young brands. This is good news for budding designers with budget constraints who also wish to produce at a sustainable pace.

Look through a factory’s catalog or previous customers’ orders, request for fabric swatches they typically work with if you have not decided on any. Typically, factories have their own fabric suppliers as well, or they can source a few that match your specifications. You should also source your own materials at the same time, and confirm that the factory is able to work with such materials before ordering.

At the end of the day, always, ALWAYS, finalise the fabrics and trims yourself, even if you have to be guided by the factory. It does not guarantee that the end product will be flawless, but at the very least, if the garment does not come out as expected due to the fabric, you would have learnt from your mistake. Every mistake that you make in garment production is a valuable lesson.

Having chosen the materials you would like to work with, a prototype can be made with the materials and trims of your choosing. A muslin sample should be made prior to that if there is significant changes to existing design, especially in terms of silhouette and construction. Actual production can begin once you are happy with the final prototype (and several rounds of testing, which I will address later on). Never before that, especially if you are producing sizeable quantities. The factory’s final prototype serves as the benchmark of quality, and you as the client has to set your tolerance for deviation based on the final prototype (which the factory can accept/refuse/negotiate).

B. Start from Zero

For those who are keen to start from the beginning – either due to the sheer complexity of the design, or unable to find contractors with a suitable catalogue – you could still engage a factory, or individual contractors who can carry out each specific stage of the production process. These days you can find freelancers on websites such as upwork.com and fiverr.com.

Common practice dictates that a typical factory will stipulate a minimum quantity for production, a number which can be difficult to achieve. If you are not interested in engaging the service of a factory, there are small workshops and sewers who can produce garments a handful of pieces at a time, depending on your location.

Cost per garment will be much higher since smaller contractors cannot take advantage of certain equipment and division of labour that only large manufacturers can employ. In a small workshop, cost of manufacturing is highly dependent on the number of hours spent on individual garment. Most of the labour goes towards fabric cutting which is often done by handheld shears, as opposed to a vertical knife that can cut through 50-100 layers of fabrics.

Regardless of the route taken, it is necessary to ensure that you have done the preparations required to ensure your contractor knows exactly what you want them to do. And it begins with your tech pack.

From your fashion drawing (or collage of details), a freelance illustrator can do a flat drawing of your garment proportionate to the measurements provided, including the technical specifications and intended fabrics, trims, embroideries etc, all of which should go into the tech pack. It is a document that includes ALL the information needed to produce the garment. The less you indicate, the more guesswork your contractors have to do. They will fall back on standard practices on anything you don’t indicate, and it may not be what you have in mind.

If you have decided to work with a factory, they would have in-house patternmaker(s) and sampling team who can produce the prototypes. The other option would be to hire a freelance patternmaker who can create electronic patterns which you can forward to a professional tailor or sewer of your choosing. For complex garments, a muslin sample is recommended, or use cheap fabric substitutes that have similar quality to the final fabrics, before making the final prototype. I usually make 2-3 prototypes in different fabrics so I will know which one would be the most suitable option, especially when judging by aesthetics, comfort and other practical benefits. I would also recommend making the final prototypes in two different sizes.

Final Stage of Production

While the first prototype is being made, it is advisable to prepare all the tags and labels to be attached on the garments so that they will be ready when the production begins.

Between the completion of final prototype and actual production, it is important to test your garment by wearing it a few times, and if necessary, putting it in the wash and drycleaners to test for shrinkage and colour fastness. As a rule, I pre-shrink cottons and linens before cutting. If there is significant shrinkage, that fabric goes into the bin.

Size grading should be finalised before production. You can either attempt to do it yourself in very limited instances (such as making a 2-3 sizes-fit-all type of simple garments), or seek the assistance of a professional (patternmakers often double as patterngraders). This goes into the final version of the tech pack.

Bill of Materials – attached together with the final tech pack and electronic/paper patterns – is extremely important so that the contractor knows exactly what each garment component is made of. Some contractors even need you to supply your own threads. While there are softwares to make the BOM, a factory will not turn down one that is created on Excel; it’s all about delivering clear, concise and complete information. Cover all bases, and that includes annotating the face and back of fabrics! Mark and scan the swatch if you can’t send the physical version of the tech pack. And if you decide to be unorthodox with your material use by using the back of the fabric as the face, then you need to make sure that the contractor and their mothers and fathers and aunts and uncles are aware of it.

If you are producing overseas, it is important to be aware of regulations when it comes to import regulations and custom duties, as well as delivery terms (EXW? FOB? DDP? More jargons to familiarise yourself with). A box of 5 jackets can easily be shipped by major courier companies door to door. A box of 100 would require several extra steps for import clearance, as well as freight and insurance. More often than not, you would need to do it under a company name, so if you have not registered your business at this point, you would have to appoint a third party logistics company to assist in custom clearance.

Be Prepared for Setbacks

When I first started making ROSEN-X, I had engaged both factories and independent professionals to do samples. There were hits and misses from both, but more misses from the factories because of my lack of experience. I have found that factories trust that you know what you are doing the moment you give them the tech pack, or failing that, technical illustrations. They will not spend the time to advise you on where certain things might not sit well, or drape the way you imagine it, because it is not their job. The onus is on you to confirm every single detail that goes into a garment. A small sewing workshop would usually take the time to ask for clarification if something isn’t clear, up to a degree.

This is why I stress the importance of starting with what you know, then move forward one step at a time. Many of my early design failures stemmed from not conveying enough information to the contractors, especially when it comes to the invisible components of a garment. I did not know what I did not know, until saw the result of my ignorance. As valuable as mistakes can be, you would need to consider how many you can afford to make as every single one costs time and money. Much of what goes into making garments beautiful are hidden from the outside; from seam finishes to interfacing, from padding to stitching tension. If necessary, seek out the expertise of a freelance garment technologist to improve on sub-par prototypes.

Despite all the precaution that you have taken, there would be baffling issues that crop up. Anyone who has made clothes for some time has their own horror stories to tell. Here’s mine. A factory that has been commissioned to make a pair of jacket and pants had been given the paper patterns and final samples that my freelance sewers had done. All they had to do was make identical copies with finishing details done on equipment that only certain factories possess; finishing that should be done at the final stage of construction. The samples came back 2 sizes larger, and to this day I still don’t know why because they failed to provide a reason for their mistake. While I can tolerate mistakes, I cannot accept a lack of accountability. Needless to say I did not continue working with them.

To protect yourself from nightmare scenario, your Purchase Order must outline what your tolerance is, and what the contractor’s obligations are should they deviate from your instructions. At the very least you will find yourself laughing in puzzlement rather than crying when such incredulous situation invariably occurs.

Finding A Suitable Contractor is An Arduous Journey

It is important to seek contractors that specialise in your desired styles or textiles. Just like how some garments require certain skillsets to sew and finish, so do materials. For example, if you’d like to make a silk bomber jacket, a contractor skilled in handling delicate fabrics would do a better job in sewing and finishing than a contractor who typically makes bomber jackets but rarely work with silk. Likewise, a contractor who specialises in making fashion-forward clothes may not necessarily have the tailors and equipments to make a sharp suit jacket. ROSEN may be a modest-sized company but we work with 4-6 contractors of varying sizes at any given time, each with their own expertise.

You might also find that some contractors will say yes to your project, only to produce sub-standard quality because they were unable to work with your materials, or they simply have shoddy workmanship. The tales of contractors biting more than they can chew is not rare in this industry. There is no shortcut to finding the right contractor other than to try several candidates at the same time, especially if you want to make complex garments.

Disclaimer

While I had done my best to be as concise as possible, this guide is written as a simplified version of standard industry practices, geared towards fashion design entrepreneurs who are most likely doing direct sales to consumers. In reality, every step of the process can be expanded in detail. Conversely, you can also skip a step or two if it is not relevant to your business model. And if you are doing wholesale retailing, there are more requirements that would be stipulated by retailers. Every single item on the pre-production checklist could fill up a book. The larger the operation, the more formal the paperwork has to be in order to ensure a smooth flow from one work station to the next. However informal the format of your documents are, there is no getting away from presenting accurate and detailed information that you want your contractors to be aware of.

Epilogue

Before getting overly excited about producing a clothing line, it is important to take a good hard look at whether embarking on a clothing business venture is worth your while. Do your own cost-benefit analysis. What comparative advantage do you have currently within your environment? What disadvantages do you have to overcome?

The primary reason why I started ROSEN was because I had moved to China where I am now in close proximity to small-scale garment workshops and material vendors who have no issue servicing small business and producing in low quantities. I do not have to deal with import issues, unless I am ordering materials from overseas. Domestic logistics are seamless and lightning fast, which cuts down on transit time for movement of materials and finished goods. The major homework that I had to do was sift through hundreds of material suppliers and contractors who are willing to provide production value I am aiming for, and constantly reminding all my production partners of the quality I expect from them.

Production is only a small part of a fashion brand’s ecosystem. The old adage of “Build It And They Will Come” is no longer applicable in the 21st century fashion industry. There is still the matter of logistics, customer service, brand-building, marketing, PR, accounting and a whole lot more, such as the unquantifiable acumen of having the vision and taste that resonates with your audience. But you have to build something nevertheless, before you can get on your soapbox and do your marketing yodels.

I have written this guide from my personal experience as someone who plunged into the industry on her own, with no financial backing from investors, and no production team to speak of in the beginning. I was however, educated in business and economics, which has helped me greatly in the operations department. Though I may not have the technical skills to make a piece of clothing from scratch, by the time I started ROSEN, thousands of designer archive pieces had passed my hands, so I had built a mental inventory of what a high-value garment should feel like on the body. On the other hand, my lack of technical knowledge in the beginning had caused me to make many mistakes. I had to toss many samples as they were not good enough. Even if the rule book of accounting can dress it up as R&D investment, at the end of the day, it was still my capital that I had lost.

Building your own label is not a shortcut to fame and fortune. Whatever mistakes that a fashion student make in school, you might probably make them in the real world. There will always be a price to pay somewhere down the line. Can that loss be recouped by the sales you are projecting? If the answer to that question is yes, then I hope you find this guide useful one way or another.