Ask someone to name the greatest designer to come out of Japan, Rei Kawakubo would probably be recalled as often as Yohji Yamamoto. But twenty years ago, someone else’s name would have been brought up equally often. That man is none other than Issey Miyake.

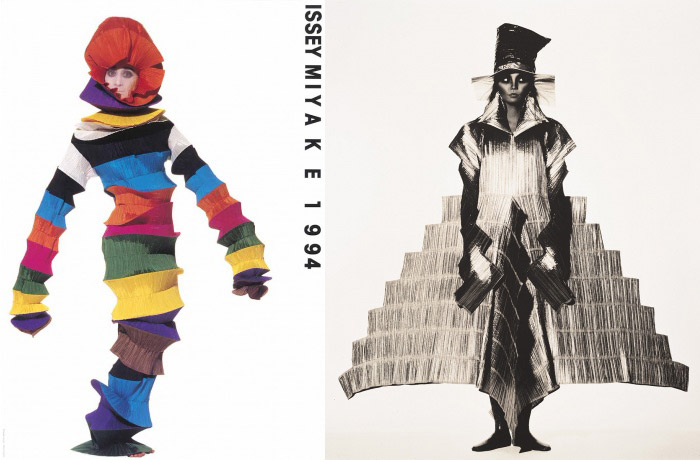

Miyake-san, a Hiroshima survivor, did not have any formal training in fashion design. Like Rei Kawakubo in Comme des Garcons, his works took the Parisian runway by storm because they were vastly different from the Western aesthetics. Back in the 80s, while Alaia and Mugler set the trends with their clingy bodycons and power dressings (big shoulders, tiny waist), Issey Miyake’s direction played with the idea of space, much like the Japanese kimono but not necessarily its silhouette per se. Words that are best used to describe his works are billowy and gravity-defying. Even though they are as structured as Cristobal Balenciaga’s bubble coats, Issey Miyake’s creations appear so much lighter next to Balenciaga’s.

Issey miyake was an expert manipulator of exaggerated shapes. While the West was obsessed with the rise of hypersexuality and female sexual empowerment, Miyake-san focused on creating works of wearable art. He saw clothes as more than a form of coverage that accentuates the female body championed by the Western standard of beauty (curvy, prominent breasts and derrière), they were art pieces that changed according to the shapes and sizes of individual wearers. In many ways they were more of a liberation – that the feminist hypersexual norm of beauty the Western fashion advocated – than the typical Parisian designers, as can be seen by comparing Miyake-san’s coat next to Alaia’s figure-hugging romper. This happens to be a common theme among the other Japanese designers. Their garments mould their shapes according to the wearers, whereas the Western designs require the wearer to mould their bodies according to the garments. How many of us strive to lose pounds on the treadmill just to fit into a skin tight dress?

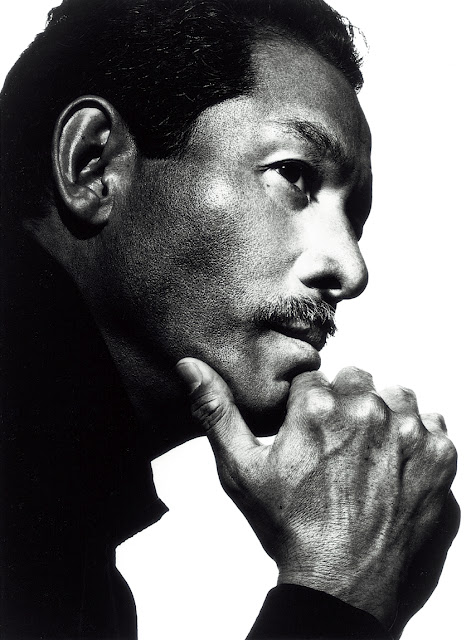

Issey Miyake had always chosen the legendary Irving Penn to capture his works. The relationship began in 1983 when the photographer first shot Miyake-san’s clothes in 1983 for American Vogue. Since then Miyake-san had always trusted the photographer to document and interpret his works according to his whim, never once being in the same room with Irving Penn himself. “I did not want to interfere with his freedom,” Miyake explained when asked why. “I wanted to see what he would do!”

Throughout the 80s and 90s, Issey Miyake continued to produce works of wearable art that never failed to outshine the one before. In 1993, the sub-division Pleats Please was born, whose pleats has become the parent brand’s signature look. Just in case you’d like to know how they were made, it involves heat-treating polyester jersey to permanently retain washboard rows of horizontal, vertical or diagonal knife-edge pleats. The fabrics are cut and sewn first, then sandwiched between layers of paper and fed into a heat press, where they are pleated. The fabric’s ‘memory’ holds the pleats after the garments are liberated from their paper cocoons.

Miyake-san retired in 1999, but continued to work on research in fabric technology and other design projects. There are now different subsidiaries under Issey Miyake aside from the Pleats Please line, such as A-POC and Issey Miyake Fête.

what a great read – definitely saved into my bookmarks.

i completely agree with the statement that you make in the beginning..it’s amazing that not many people are aware that Miyake’s presence was significant far prior to Rei and Yohji’s.

Fantastic post. Miyake makes incredible shapes. I am fascinated by the pleats.

The ssey Miyake ‘Seashell’ Coat would have to be my favorite as well. The texture and shape are perfect.

Great post. Show Miyake’s designs to strangers walking down the street and most would refer to the more outrageous pieces as ugly. However, while it doesn’t take a fashion genius to make ugly clothes, it takes a brilliant mind to create designs most people can’t understand (myself included, I admit).

he is definitely an artist.

http://wildsidefashion.wordpress.com/2014/04/04/issey-miyake-covek-koji-je-preziveo-atomsku-bombu/

The artistry of the man…. What a wonderful page. Thanks for sharing.

It’s wrong that he’s not featured in v ogue.com and that he’s off the radar. On the contrary the last 2 years the collections are fabulous and featured on vogue.com and many other sites. The bag brand Bao Bao is also coming strong.